Essays and Conversations on Community & Belonging

The Knowledge Problem Problem

Ideology offers the seductive comfort of certainty, encouraging "motivated cognition" where we force evidence to fit pre-existing beliefs. The antidote is not a rejection of principle, but Radical Moderation. Grounded in Hayekian humility, this approach respects the limits of central planning without weaponizing doubt to justify paralysis. It recognizes that a stateless society yields not freedom, but the "Rule of the Clan," and that true liberty requires a capable state to prevent private coercion. Ultimately, moderation is principled pluralism—choosing difficult trade-offs (like a revenue-neutral carbon tax) over the "clean and well-lit prison" of dogma.

POLITICAL PHILOSOPHYSHORT FORM ESSAY

Alex Pilkington

12/20/20257 min read

Ideology is seductive because it offers certainty. But that certainty only encourages "motivated cognition," the psychological act of deciding what you want to believe and using your reasoning power to get you there. It moralizes political conflict in unhealthy ways, yielding incivility and extremism. As Michael Oakeshott warned, "Obsession with a single problem, however important, is always dangerous in politics; except in time of war, no society has so simple a life that one element in it can, without loss, be made the centre and circumference of all political activity."

The alternative is not rejecting all principles as that path leads to dangerous susceptibility and moral drift. Rather, it requires policing our inner ideologue with studied skepticism, mindful fallibility, and an inquisitive mind. It means using ideology as a guide, not a master.

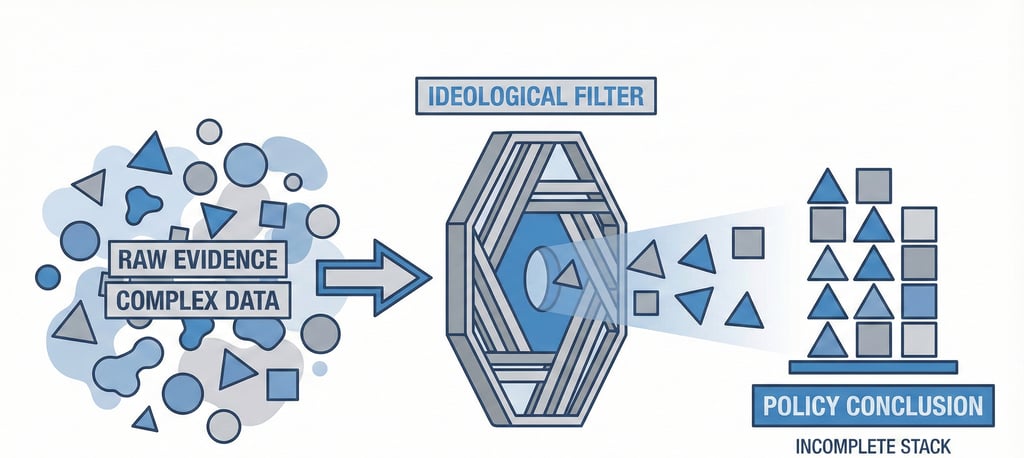

Consider how ideology distorts inquiry on climate change. In libertarian circles, climate skepticism functions as an article of faith. The evidence for anthropogenic climate change is overwhelming - ocean heat content rising, Arctic ice disappearing at rates matching model predictions, basic greenhouse physics established for over a century. Yet many folks with no training in climate science remain convinced they know better than thousands of researchers.

Why? Because libertarians view government intervention as inherently coercive, they are psychologically motivated to dismiss any evidence -no matter how scientifically robust - that suggests a need for collective action. Discussions never engage the science itself. They work backwards from the preferred policy conclusion: "Even if it's real, a carbon tax would destroy the economy."

To be fair, some within these institutions did push back. Market-oriented climate solutions exist - carbon pricing that harnesses price signals rather than command-and-control regulation. But acknowledging this required first accepting the science, which meant breaking from tribal orthodoxy. The cognitive dissonance was too great for most.

This is how ideology corrupts caring, idealistic, educated people. It breeds dogmatic thinking and lazy policy analysis. It gives birth to excessive certainty, crowding out healthy intellectual skepticism. It ignores the complexities of the modern world and threatens the pluralism that any liberal society must respect and defend. This pattern repeats endlessly across ideological divides. Whether debating health care, minimum wage laws, or Thomas Piketty's capital data, the "correct" empirical answer is always determined by pre-existing commitment. This is the death of honest inquiry.

If we reject ideology's rigid answers, we must admit the world is far more complex than any single theory can explain. This brings us to epistemological humility and to my complicated relationship with Friedrich Hayek. Hayek's core insight remains profound: central planners can never possess the dispersed, tacit knowledge necessary to order an economy or society effectively. This is a powerful argument for humility and a warning against top-down social engineering.

However, I'm wary of how this insight is deployed. For many libertarians, Hayek becomes a shield against any state action—a lazy heuristic: "We cannot know everything, therefore we should do nothing." This is a dangerous overcorrection. Epistemological humility is not a license for paralysis. It's a balancing act. We must respect the limits of our understanding while recognizing we still have moral obligations to act against clear harms.

Hayek's warning applies when systems are complex with dispersed knowledge and delayed feedback (Soviet planning, price controls). But it should be overridden when harms are clear and predictable (child labor, lead in gasoline), market failures are well-documented (externalities, monopolies), or information asymmetries favor producers (pharmaceuticals, financial products).

The moderate accepts this complexity. We can embrace Hayekian caution without accepting the dogma that the state is incapable of positive action.

When ideology blinds us to the need for state capacity, the results are rarely the "liberty" promised in textbooks. Robert Nozick's Anarchy, State, and Utopia offers many libertarians a theoretical framework for how an anarchist society would function, but it has a glaring omission: it ignores what actually happens when the state disappears.

As Mark Weiner argues in The Rule of the Clan, the absence of government doesn't yield autonomy; it yields the rule of the family, the caste, or the criminal syndicate. In cartel-controlled Mexico, citizens don't enjoy freedom, they live in terror of whichever armed group controls their territory. In Taliban-ruled Afghanistan, women cannot attend university. In southern Italy, the 'Ndrangheta became a parallel government enforcing order through violence.

The pattern is consistent: when the state recedes, power devolves to whoever can organize violence most effectively. A "stateless" society often looks less like a libertarian paradise and more like Jimmy Hoffa's Teamsters, where private force rules. The modern welfare state, for all its flaws, has often expanded liberty by freeing people from the oppression of non-governmental actors.

The ideologue will object: "Without firm principles, isn't moderation just fence-sitting?"

This misunderstands moderation. The moderate is not unprincipled - she recognizes that principles can conflict, and applying them requires judgment, not just deduction. Opposing torture is a principle. So is protecting innocent life. When these collide, pure deduction fails us.

But here's a more serious objection: implicit reliance on unarticulated ideology by those who think themselves "nonideological pragmatists" may be more dangerous than explicit ideological thinking. A self-conscious ideologue at least knows his commitments and can potentially account for his biases. The person who believes himself above ideology may think his political commitments are simply obvious truths; the result of common sense. He cannot curb his biases because he believes himself immune to them.

This is why moderation is better understood as an adjective modifying a noun, not replacing it. We should speak of moderate libertarians, moderate progressives, moderate conservatives—people who retain principled commitments but resist the temptation to make those principles absolute rulers. The moderate libertarian still values liberty; she simply rejects defining it in terms of an idealized, counter-factual Nozickian society. The moderate progressive still values equality; he simply acknowledges that pursuing it requires trade-offs with other legitimate values.

Moderation is not centrism (splitting the difference), both-sidesism (false equivalence), or value-free technocracy. It is principled pluralism and recognizes that society contains competing legitimate values (liberty, equality, community, tradition) that must be balanced rather than ranked in absolute priority.

Climate change illustrates moderation in practice. The ideological positions are familiar:

The denial position: Reject the science because the policy implications are unacceptable. If climate change is real, government intervention follows, therefore climate change cannot be real. Motivated cognition in its purest form.

The Green New Deal position: Accept the science, then propose massive government expansion - federal job guarantees, wholesale economic transformation, centralized planning. The solution must match the scale of the problem, complexity be damned.

The moderate position: Accept the science, then ask what policies actually work. A carbon tax harnesses price signals to reduce emissions without requiring planners to pick winners. It corrects the market failure (unpriced pollution) using market mechanisms. Revenue can offset other taxes, making it roughly revenue-neutral.

This isn't ideologically satisfying to anyone. Libertarians hate that it's a tax. Progressives hate that it's not comprehensive enough. Conservatives hate that it admits climate change is real. But it respects Hayekian warnings about dispersed knowledge (markets decide how to reduce emissions, not bureaucrats) while addressing a clear harm with a targeted intervention.

This isn't ideologically satisfying to anyone. Libertarians hate that it's a tax. Progressives hate that it's not comprehensive enough. Conservatives hate that it admits climate change is real. But it respects Hayekian warnings about dispersed knowledge (markets decide how to reduce emissions, not bureaucrats) while addressing a clear harm with a targeted intervention.

Florida provides a stark illustration. No state faces greater climate risk - sea level rise, intensifying hurricanes, ecological collapse. Yet some lawmakers still recite the old talking points: "I can't tell you what percentage is due to human activity." Meanwhile, we see what happened with the state's home insurance premiums in recent years. All this money spent on repetitive loss properties every time there's a hurricane has made it unaffordable. An ounce of prevention is better than a pound of cure.

The moderate recognizes that inaction has costs too. Tourism and fisheries collapse. Federal disaster spending spirals. If we do not take care of our environment, it's going to hurt our economy. This isn't about destroying the economy to save the planet, it's about acknowledging that climate change is already destroying both, and that smart policy can address it without requiring wholesale government control.

What is the alternative to ideology? There is no easy answer. Without some means of sorting information, we would be overwhelmed and incapable of considered thought. Without any underlying principles, we are dangerously susceptible to believing anything. Yet any coherent set of beliefs contains the wet clay of ideology.

The best we can do is police our inner ideologue with studied skepticism, mindful appreciation of our fallibility, and an open mind. This requires humility, prudence, and pragmatism. It means recognizing that remaking society in some ideologically-driven image threatens the pluralism that a liberal society must defend. A sober appreciation of knowledge's limitations—and the irresolvable problem of unintended consequences—further cautions against over-ambitious policy agendas.

I began this philosophical journey searching for a system that could answer every question. I found instead that the best questions have no systematic answers. They require judgment, trade-offs, and the humility to say "I don't know" when certainty is unwarranted.

This isn't satisfying for those raised on ideological certainty. There's no moment of conversion, no single text that provides the key. There's only the daily work of thinking clearly, weighing evidence honestly, and resisting the seductive pull of systems that promise to do our thinking for us.

The moderate's path is harder because it cannot be systematized. It requires constant vigilance - not just against the arrogance of ideologues, but against the hidden biases of those who think themselves above ideology. The prison of ideology offers bright lights and clear walls. The path of moderation is darker and more difficult. But it's the only path that leads to truth while preserving the pluralism essential to a free society - and the only one that keeps us honest about the limits of what we can know and what we should attempt.