Essays and Conversations on Community & Belonging

Blaming the Protocol: Why Critics Miss the Point on Crypto

This piece analyzes Finn Brunton's recent New York Times critique against cryptocurrency, arguing that he commits a fundamental category error. This piece first deconstructs the rhetorical frames used to associate the technology with political corruption, then provides a rebuttal from first principles and contrasts the failures of centralized human actors (the "industry") with the technology's core goal of trust minimization (the "protocol").

SOCIAL & POLITICAL COMMENTARYTHE FRACTURED REPUBLICSYSTEMS & INCENTIVESTHE ALGORITHMIC CAGEGOVERNANCE & ECONOMICS

Alex Pilkington

10/31/20254 min read

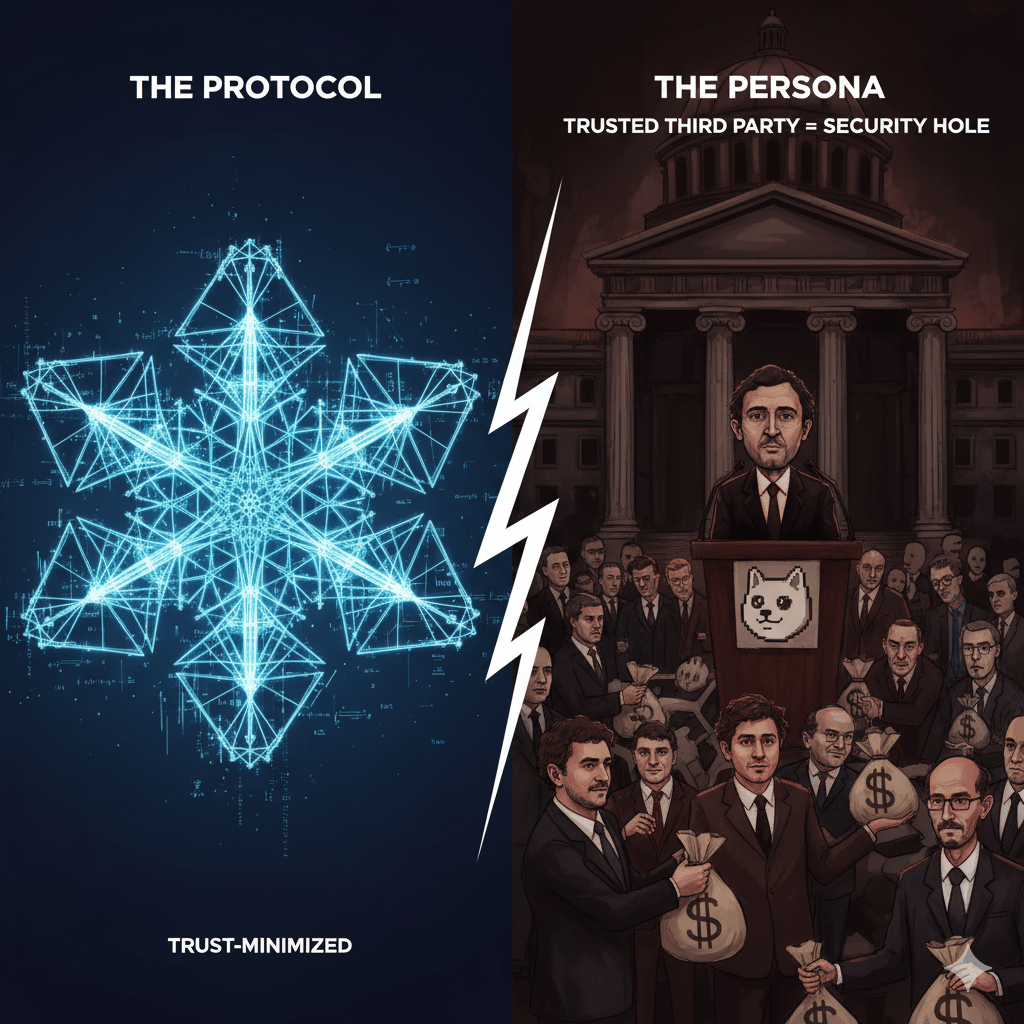

Protocol vs. Persona

Finn Brunton's New York Times article "Crypto is the most successful libertarian project in American history" presents a powerful, searing narrative: cryptocurrency, it argues, is not a financial innovation but a political weapon. It posits that the technology's stated goal of freedom was merely a smokescreen for its true purpose: to remove all checks on the wealthy, enabling a new autocracy led by political figures like Donald Trump and Silicon Valley elites like Peter Thiel.

This argument is effective because it skillfully employs a series of uncharitable rhetorical frames to associate the technology with its worst actors. Before addressing the technological premise, it's essential to deconstruct this narrative strategy.

First, the article relies on guilt by association. It opens not with a discussion of the technology, but with a gala at Trump's country club, immediately placing cryptocurrency in the same room as a $TRUMP memecoin and Justin Sun, a billionaire under investigation for suspected financial crimes. This taints the entire subject with political polarization and criminality before any technical argument is made.

Second, it employs a strawman of libertarianism. The philosophy is reduced to a "clown show" by exclusively highlighting its most extreme, socially toxic and most fringe positions - such as opposing laws against "child labor" or "racial segregation." This caricature is then used as the corrupt ideological seed from which crypto allegedly sprang, allowing the author to dismiss the technology as the offspring of a toxic and unserious philosophy.

Third, the author engages in malicious motive impugning. The article does not argue that crypto failed in its goals; it argues its goals were always a lie. The desire for freedom is framed as a disingenuous cover for the real goal: "removing all checks on the power of the wealthy... even if the result is autocracy." This allows the author to portray any proponent as either a fool or a would-be tyrant.

Finally, the author's most potent argument is a "true purpose" fallacy. The article observes the chaotic, human-driven industry: the frauds (FTX), the criminal use (Silk Road), the political lobbying (Thiel, Andreessen), and the speculative gambling (memecoins) and concludes that this is the technology. The capture of the industry by political elites is not presented as a failure or co-option of a neutral tool, but as the intended fulfillment of its "darkest potential." The article frames the problem (political capture) as the product.

Rebuttal

This entire narrative, while politically compelling, rests on a fundamental category error. To understand this, one must look at the work of Nick Szabo, the computer scientist and legal scholar who designed Bit Gold (a direct precursor to Bitcoin) and smart contracts. A rebuttal from his perspective would find that the article is not critiquing cryptocurrency at all; it is critiquing the very human failures his work was designed to solve.

The core of Szabo’s philosophy is trust minimization. His foundational paper, "Trusted Third Parties Are Security Holes," argues that relying on humans and the institutions they run (banks, governments, legal systems) is the primary vulnerability in all commerce and law. These "trusted" parties are susceptible to corruption, coercion, and error.

Szabo's entire goal was to replace the fallible, trust-based code of human law and institutions with the verifiable, trust-minimized code of software. The article's critique perfectly illustrates his thesis: it is an exhaustive list of trusted third parties failing. Sam Bankman-Fried, Donald Trump, Justin Sun, and venture capitalists are not examples of crypto; they are security holes in human form, the very problem Szabo was trying to design around.

A Szabo-centric rebuttal would make three key points:

The Article Confuses the Protocol with the "Industry." The author conflates the decentralized, automated protocol (like Bitcoin) with the centralized, human-run industry (like FTX, Binance, and the $TRUMP memecoin). The protocol is a set of rules without a ruler. The industry is a collection of traditional, centralized companies that act as trusted third parties, complete with CEOs, marketing departments, and political lobbyists. The article’s villains are all centralized actors who re-introduced trust into a trustless system. Blaming the protocol for the failures of the industry is like blaming the invention of the TCP/IP internet protocol for phishing scams and email spam.

The $TRUMP Memecoin is the Antithesis, Not the Apex. The author presents the memecoin gala as crypto's ascension. From Szabo’s perspective, this is the technology’s absolute nadir. A memecoin is the antithesis of Bit Gold. It has no unforgeable costliness, its value is tied entirely to a central personality, and it relies on pure social trust and hype. It is a centralized, speculative token, no different from a casino chip. Szabo’s goal was to create a politically neutral, unforgeable, trust-minimized digital commodity whose value was independent of any person or government.

The Author Misunderstands "Freedom" as Autocracy. The article frames the libertarian desire for freedom as a desire for a "nerd-warlord society" or "autocracy." Szabo’s concept of freedom is social scalability. This is the ability for a system to grow and allow strangers from different cultures and jurisdictions to cooperate and transact without needing to trust each other or a central authority. The goal is not to create an elite, but to disintermediate the existing ones by creating a global, neutral financial and contractual layer that is resistant to their political capture. The article simply describes the old-world system of political capture and mistakenly blames the new-world tool designed to escape it.

In conclusion, the article provides a powerful critique of the ways in which a new technology has been co-opted, corrupted, and weaponized by powerful human actors. But it fails to understand that it is describing the disease, that is the fallibility of human trust, while blaming the medicine.