Essays and Conversations on Community & Belonging

Beyond Marriage and Markets: A Radical Liberal Case for Queer Emancipation

Mainstream LGBTQ victories have left the most vulnerable behind, masking the ongoing "administrative violence" of the state. Nathan Goodman argues that by applying Public Choice economics, we see how the government is incentivized to militarize against marginalized communities due to asymmetrical transaction costs. The solution isn't socialism or more lobbying, but a "Radical Liberalism." We must build bottom-up institutions of mutual aid and voluntary association to bypass state power entirely and create true emancipation.

SOCIAL & POLITICAL COMMENTARYGOVERNANCE & ECONOMICSSUBCULTURE & COMMUNITYSYSTEMS & INCENTIVESTHE KNOWLEDGE PROBLEMTHE FRACTURED REPUBLIC

Alex Pilkington

1/5/20264 min read

For the last decade, the mainstream LGBTQ movement has celebrated a series of monumental legal victories. From Lawrence v. Texas to Obergefell v. Hodges, the strategy has been clear: secure formal equality under the law. But as the confetti settles, a growing number of radical voices are asking a difficult question: Who was left behind?

Legal scholar Dean Spade argues that an excessive focus on "what the law says" often masks the brutal reality of "what the law does". Anti-discrimination statutes do not stop the "administrative violence" of poverty, deportation, and incarceration that disproportionately targets trans people of color and those in the underground economy. In seeking inclusion in institutions like the military or the police (via hate crime laws), the mainstream movement has inadvertently strengthened the very systems of state violence that threaten its most vulnerable members.

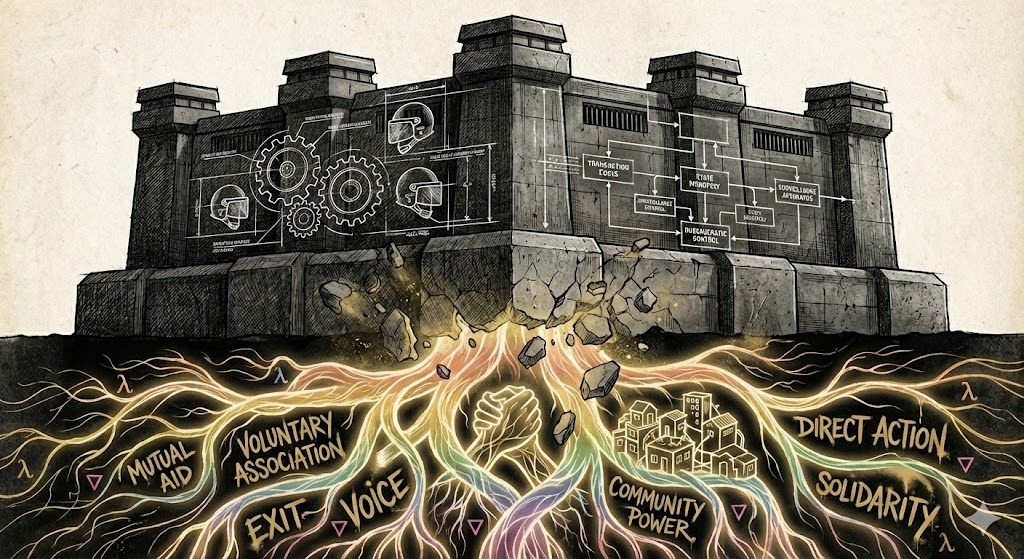

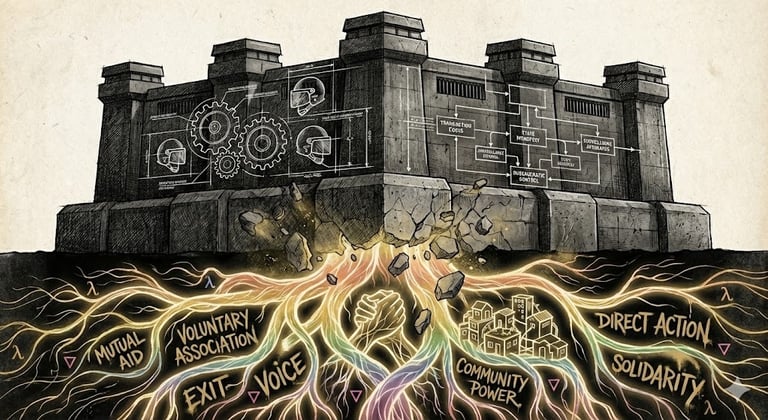

If liberal legalism has failed the marginalized, and the state itself is the engine of oppression, where do we turn? The answer may lie in an unexpected synthesis: Radical Liberalism. In a recent paper entitled "A Radical Liberal Approach to LGBTQ Emancipation" by Nathan Goodman, he argues that by combining the fierce anti-authoritarianism of queer radicals with the "mainline economics" of Public Choice Theory, we can chart a path toward true emancipation—one that relies not on the benevolence of the state, but on the power of exit, voice, and voluntary association.

The Economics of Enforcement: Why Militarization is Cheap for the State

To understand why our domestic police forces increasingly resemble occupying armies, we must look beyond mere ideology and examine the grim economics of political exchange. The militarization of our streets is not an accident; it is the predictable output of a system defined by asymmetric "transaction costs"—the time, resources, and social capital required to negotiate and enforce political agreements.

In the current system of "political capitalism," there is a stark divide in how easily different groups can influence state violence. On one side, we have the "insiders": legislators, Pentagon officials, and lobbyists for defense giants. These actors operate in a world of vanishingly low transaction costs. They move through the same social circles and "revolving doors," making the negotiation of policies—like the transfer of military gear to local police via the 1033 Program—as frictionless as a handshake.

This ease of transaction creates a "boomerang effect". The weaponry and aggressive tactics developed for foreign interventions inevitably recoil back onto the domestic population. Because the benefits of these transfers are concentrated among a small, cohesive group of contractors and bureaucrats, they have a powerful incentive to invest resources in keeping the machinery of militarization humming.

On the other side of this divide are the "outsiders"—ordinary citizens, and specifically, the marginalized LGBTQ communities often targeted by this machinery. For us, the transaction costs of resistance are prohibitively high. Unlike the defense lobbyist, the average citizen faces immense hurdles just to have their voice heard. We lack the resources and the institutional access to effectively bargain against the state’s acquisition of power.

This asymmetry is lethal. When a marginalized community is policed by a SWAT team using tactics imported from a war zone, they are trapped in a brutal equilibrium: the state militarizes because it is cheap and easy for the ruling class to do so, while stopping it remains expensively out of reach for the people most likely to suffer its consequences.

The Economics of Survival: Voice, Exit, and the Margins

Caught in this snare of state power, marginalized people face two primary mechanisms for improving their condition: Voice and Exit.

"Voice" is the ability to influence political outcomes—voting, lobbying, or protesting. But as we have seen, the political market is rigged. Marginalized groups often lack the capital to lower the transaction costs of political exchange, rendering their "voice" structurally muted.

This leaves "Exit"—the ability to withdraw from a bad situation, to move to a jurisdiction or market that treats you better. In a functioning market, exit is the ultimate check on tyranny. But for the most vulnerable queer and trans people, the cost of exit is often insurmountable. Without savings or stable employment, one cannot simply move away from a hostile police precinct or an oppressive state. Caught between a political system they cannot influence and a jurisdiction they cannot afford to leave, they become sitting ducks for state violence.

However, there is a third option: Creative Exit.

Radical liberalism suggests we can lower the cost of survival by creating "endogenous rules" and institutions that bypass the state entirely. This is the heart of prefigurative politics. We see this in the Audre Lorde Project, which organizes "safe neighborhood campaigns" to resolve conflicts without calling the police. We see it in trans communities that use mutual aid to route around state-controlled medical monopolies to access gender-affirming care.

These are not just acts of charity; they are acts of economic defiance. They effectively create a "market" for safety and care where the state has failed, allowing people to coordinate from the bottom up.

Why Not Socialism?

Given the failures of capitalism, many radicals instinctively turn toward socialism or Marxism. Yet, economic theory warns that this is a dead end.

The "calculation problem" reveals that without markets and prices for productive goods, central planners cannot effectively coordinate scarce resources. A system that abolishes private property destroys the very feedback mechanisms needed to determine if resources are being used effectively, leading to chaos and poverty that inevitably harms the most vulnerable first.

Moreover, history is a harsh teacher. Regimes that centralized economic power—like Castro’s Cuba—often centralized social repression as well. The Cuban revolution viewed LGBTQ identities as products of bourgeois decadence, erasing the "profit incentive" that had previously allowed gay bars and queer spaces to exist even in a homophobic society. By concentrating power in a "vanguard," socialism recreates the very dangers of discretionary authority that abolitionists rightly fear in the police and prison systems.

Conclusion: A Radical Liberal Future

The solution to the dysfunctions of the liberal state is not less liberalism, but radical liberalism. We must push the liberal commitments to voluntary association, individual rights, and experimentation to their logical conclusion.

This means abolishing the state monopolies on money, land, and security that underpin "political capitalism". It means rejecting the "entangled" economy where corporations and the state conspire to extract rents from the people. And most importantly, it means building a world where social order arises not from the top-down commands of a policeman or a planner, but from the bottom-up cooperation of free individuals.

In this radical liberal vision, our neighbors are not enemies to be policed, but partners in a "catallaxy"—a spontaneous order that turns strangers into friends.